|

|

To Hell and Back: Wake During and After World War II by Dirk H.R. Spennemann |

|

|

To Hell and Back: Wake During and After World War II by Dirk H.R. Spennemann |

In mid-1930s the major airlines of the U.S.A. as well as Japan investigated the feasibility of long-distance flights across the Pacific.

Wake and the trans-Pacific airroute In November and December 1935 Pan American Airways sent its 25-ton seaplane China Clipper on a successful flight from San Francisco to Manila, via Honolulu, Midway, Wake and Guam. Following this inaugural flight, a regular fortnightly service was introduced in 1936, using Boeing planes from 1937 onwards.

Between 1935 and 1937 Pan Am Airways set up a complete establishment on Wake Island, comprising a hotel/inn, stores, a power plant, radio station and a refridgeration unit, as well a living quarters for the ground crew servicing the aircraft. [1] The development of Eneen-kio into a civilian airstation in the late 1930s also brought along the attempt to grow fresh vegetables in hydroponic cultures. On record are lettuce, tomatoes, squash and beans. [2]

Wake as a Naval Air Station Although Wake had been developed primarily as a civil air station, its status changed to a naval air station by Executive Order in 1935. Some, but very little development took place, as the development of other naval air stations had a higher priority. In 1939, then, the U.S.Congress allocated $2 million to the Secretary of the Navy to develop Wake Atoll into the airstation as desired. [3]

Figure 1. Location of the Republic of the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean. The frame shows the area covered by figure 2.

Wake as a National Defense Area On February 4, 1941, President Roosevelt signed an Executive Order making Wake Island a national defense area. The development of the air facilities, as well as of coastal defense structures was given high priority. A total of about 1100 civilian contractors worked on Wake.

Figure 2 Location of Eneen-kio in relation to the rest of the Marshall Islands

In this brief overview I will discuss the attack on Wake, but I will also address the Japanese occupation of the atoll in its background of the Japanese military presence in the Marshall Islands. The fate of the Japanese garrison facing a U.S. war of attrition will also be discussed.

In November and December 1941 the development of Wake Island into a fully operational air station was still in full swing but far from complete. In view of the increasing friction between the Japanese and the U.S., the defensive efforts were increased. On December 4th a contingent of naval fighters was flown off U.S.S.Enterprise to provide protection. [4] In a similar preventative move all wives of the Pan American Airways and civilian contractor employees hitherto staying on Peale had been ordered to leave the island on November 1, 1941, by order of the Navy. [5]

Forces stationed on Wake in November and December 1941 Overall command of the garrison was under Major James P.S. Devereux, U.S.Marines, from end of October 1941 and under Commander W. Scott Cunningham, USN, from November 28th, 1941, onwards. Cunningham, as the Island commander, also had overall responsibility for the development of the air station and for negotiations with the civilian contractors, represented by Dan Teters. [6]

The build-up of forces had progressed slowly and by early December the following forces were stationed on Wake: the 1st Marine Defense Battalion under command of Major James P.S. Devereux, the Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-211 under the command of Major Paul A. Putnam comprising 12 Grumman F4F Hellcats. [7] the naval base detachment under command of Commander W. Scott Cunningham and a small detachment of the Army Signal Corps, commanded by Major H.Wilson, to assist the ongoing ferrying operation of B-17 bombers to the Philippines. In addition to these military personnel there were some 1100 civilians on the island, all but a few working for the Contractors Pacific Naval Bases. [8] The remaining civilians were employees of Pan American Airways operating the Clipper base. Table 1. shows the strength of the Wake garrison in early January 1941.

Table

1. Strength of the garrison on Wake on 8 December 1941.

[9]

| Unit | Officers | Enlisted men | Civilians |

| 1st defense Battalion Detachment | 15 | 373 | -- |

| VMF-211 and attachments | 12 | 49 | -- |

| Naval air station | 10 | 58 | -- |

| Army Signal Corps | 1 | 5 | -- |

| USS Triton [10] | -- | 1 | -- |

| Contractors Pacific Naval Bases | -- | -- | ~1100 |

| PAA employees [11] | -- | -- | ~70 |

| PAA passengers [12] | -- | -- | 1 |

| Total | 38 | 486 | ~1200 |

The state of the Wake naval air base at the outbreak of the hostilities At the time of the Japanese attack the development of Wake Atoll Naval Air Base was still under way and far from complete. Although a number of structures had been built, the defensive systems were far from complete. For example, the ere was no radar and a number of the gun batteries lacked the height finders or the gun directors.

U.S. contractors had completed the living camps, camp 1 at the southwestern end of Wake and camp 2, where also the contractors the hospital was located, at the northwestern end of the same island; camp 1 housed the marine garrison, while camp 2 housed the civilian contractors. [13]

Completed were also the road network of compacted coral, the main east-west runway, the clearings for the other two runways as well as for the plane dispersal/parking areas, the fuel storage and ammunition dumps on Wilkes and a seaplane ramp on Peale. In addition, a number of gun batteries had been emplaced by the U.S. Marines, one at Toki Point on Peale (battery D; 3" AA guns), one on the southwestern end of Wilkes (battery L, 5" CD guns), one at the shore in the centre of Wilkes (battery F, 3" AA) and two batteries at the southeastern point (Peacock Point) of Wake island proper (batteries A & E). [14]

The aircraft revetments had almost been completed, but not in time for the first Japanese attack.

Extension of the base facilities As had been mentioned earlier on, the U.S. had intended to utilise Wake also as a submarine base. To that end the U.S. engineers and civilian contractors had planned to dredge a deep-water channel to facilitate access to the lagoon. For this purpose a dredge, the Columbia, was brought from Honolulu with the initial complement of engineers in the William Ward Burroughs. [15] For the meantime, as a expedient measure, the existing channel between Wilkes and Wake Islands was to be deepened. Once this was completed, attention shifted to the dredging of a completely new channel, to be cut across the centre of Wilkes Island. The work on this channel began after May 1941, [16] and was still in full swing in December 1941. The channel is partially visible as a cleared and partially dredged area on the aerial coverage of 3 December 1941, the last aerial photos shot of Wake before the outbreak of the Pacific War. [17] Construction was halted after the begin of Japanese attacks, although the U.S. Navy wanted a continuation of the work almost at all costs. [18]

The day of Pearl Harbor The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 8th, 1941, [19] was partially launched from bases in the Marshall Islands. Not only came the submarines providing the submarine screen from the base of the 6th submarine fleet in Kwajalein, [20] Pearl Harbor I-24 but also several flying boats taking part in the Pearl Harbor as well as in the raids on the U.S.bases on Wake I., Howland I. and Canton I. were launched from the seaplane bases of the Yokohama Kokutai (later 802nd Kokutai) on Wotje, Majuro and Jaluit. [21]

Wake in December 1941 Bombing raids to "soften up" the garrison on Wake occurred on December 8th, 9th and 10th, always between 11:00 and 12:00h. The bombers came from bases in the Marshall Islands, where they must have taken off just at of soon after dawn in order to arrive at Wake by noon. The bombers of the first attack on December 8th were 36 Mitsubishi G4M "Betty", and belonged to the Air Attack Force No. 1, 24th Koku Sentai (Air flotilla), based on Roi, Kwajalein Atoll. The attack concentrated on the airfield and at the end of the attack, eight of the twelve U.S.fighter planes had been destroyed, [22] as had been fuel tanks, aviation spare parts and most of the oxygen, thus severely curtailing the efficiency of the U.S. air cover.

The first assault On December 11th, between 3:30h and 5:00h in the morning the Japanese conducted a landing attempt which was precluded by naval shelling. A task force of 13 vessels, under the command of Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajoka, had departed Kwajalein the day before. The fleet consisted of 3 cruisers, 6 destroyers, 2 patrol boats and two transports. In addition, some submarine patrolling and reconnaissance was conducted in advance of the incoming fleet. The submarines apparently also provided navigational guidance for the land-based bombers attacking from bases in the Marshalls. [23]

The Japanese landing operation was considered by its planners to be easy, and a small contingent of only 450 assault troops had been collected from the bases in the Marshall Islands. [24] The assault vessels had arrived on December 3rd, from their base at Truk and sortied six days later towards Wake. [25]

Table

2 Detailed chronology of attacks on Wake Island, December 1941

| Day | Japanese actions | Effects on Wake | Related events |

| 8 Dec | ~12:00h air raid by 36 Betty bombers | Airfield bombed, seven fighter-planes of VMF-211 destroyed on the ground, numerous casualties. | |

| 9 Dec | ~12:00h air raid by 25 bombers | Naval Air Station and seaplane base bombed. | |

| 10 Dec | ~12:00h air raid by 26 bombers | Raid focussed on Peale I., Dynamite cache, including 125 tons of explosives, blown up on Wilkes with major damage to batteries on that island. | |

| 11 Dec | 5:00h landing attempt & naval shelling | Naval shelling of Wake | Two Japanese destroyers sunk, several vessels hit; the Japanese naval force retreats to Kwajalein Atoll |

| 9:00h air raid by 17 bombers | |||

| 12 Dec | ~8:00h Reconnaissance by flying boat (Mavis) | Mass burial service held | Japanese submarine bombed and possibly sunk |

| 13 Dec | |||

| 14 Dec | 3:30 pre-dawn air raid by seaplanes from Wotje | ||

| 12:00h air raid by 41 bombers (B-18-type) | |||

| 15 Dec | 18:00 air raid by 4-6 Mavis flying boats | ||

| 16 Dec | 11:00h air raid by 31 bombers | Task Force 14 sails from Pearl Harbor | |

| 17:45h air raid by a single flying boat | |||

| 17 Dec | 13:30h air raid by 27 bombers | Diesel oil tank hit as well as destruction at Camp 12. | |

| 17:50h air raid by 8 sea planes | |||

| 18 Dec | Photo-reconnaissance by single sea plane | ||

| 19 Dec | 10:50h air raid by 27 bombers | Camp 1 and PAA establishment on Peale hit | |

| 20 Dec | ~10:00h air raid by 29 divebombers and 18 fighters | 15:30 PBY arrives from Midway with information as to relief operation | |

| 12:00h air raid by land-based bombers | |||

| 21 Dec | 8:50h combined air raid by 29 carrier-borne divebombers and 18 fighters | Peale island and camp 2 hit | 7:00 PBY departs from Wake with the last US personnel to leave the atoll |

| 12:00h air raid by 33 land-based bombers | |||

| 22 Dec | 9:00h combined air raid by 33 dive bombers and 6 fighter planes | Last two US aircraft rendered inoperational | |

| 23 Dec | 2:50 Landing by the Maizuru 2nd SNLF | Wake surrenders after 12 hours of fighting | Relief task force is recalled |

Figure 3. Japanese air attack routes

Table 3. Japanese naval units involved in the first assault on Wake. [X] denotes sunk in action

| Unit | Subunit | Type | Name |

| ? | ? | CL | Yubari |

| ? | CruDiv 18 | OCL | Tatsuta |

| OCL | Tenryu | ||

| 6th DesRon | DesDiv 29 | DD | Hayate [X] |

| DD | Oite | ||

| DD | Mutsuki | ||

| DesDiv 30 | DD | Kisaragi [X] | |

| DD | Yayoi | ||

| DD | Mochizuki | ||

| ? | ? | APD | Patrol Boat No.32 |

| ? | ? | APD | Patrol Boat No. 33 |

| ? | ? | XAP | Kongo Maru |

| ? | ? | XAP | Konryu Maru |

| 6th Fleet | SS | RO-62 ? [X] |

The

naval vessels came in opening up their guns at great range. The U.S. battalions

on Wake withheld their fire until the vessels were well within range and then

retaliated. In the course of the ensuing battle between the naval vessels and

the coastal defense batteries, one of the destroyers, DD Hayate was

sunk, while one light cruiser, DD Oite, DD Yayoi, the APD

No. 33, one transport as well as the Japanese flagship CL

Yubari were hit by several 5" rounds.

The fire by the coastal defense batteries was sufficient to force the Japanese to abort the landing attempt, which already had been underway with some of the troops in the launches. The retreating naval units were attacked by the remaining planes of the VMF-211, who had conducted a fruitful search for eventually present carrier forces. Several vessels were bombed and strafed, and the DD Kasiragi was sunk in the process. Later the same day aircraft of VMF-211 surprised and sunk a surfaced Japanese submarine south of Wake. [28]

The land-based bombing raids continued after the failed landing attempt on December 11th until the day before the successful Japanese landing on December 23rd.

These lunch-time raids, which must have taken off pre-dawn on the Marshall Islands bases, were augmented by December 14th with raids by flying boats, which arrived in the evening hours.

The bombing level was maintained or increased over time. By December 20th, finally, dive bombers and fighters, both carrier aircraft joined into the battle, signalling the presence of a larger Japanese carrier task force and the imminence of another landing assault..

The relief operation The situation on Wake had become untenable as time grew on and as more and more forces were massed against it. The naval strategists at Pearl Harbor decided to send out a relief force to resupply Wake with aircraft, ammunition and men.

The relief operation was assembled on December 14th and dispatched on the 16th. It comprised vessels under the overall command of Rear Admiral Frank J. Fletcher. [29] Given the indecisiveness which ruled in Pearl Harbor and the attitude of the task force commander to play is very safe, the progress of the relief task force in the final crucial days was slow, determined by the low speed of the oiler, and was even more delayed because of refuelling operations. In the end the Task Force, only 425 miles and within plane launching distance, was recalled.

Table

4. Japanese naval units involved in the second assault on Wake

[30]

| Unit | Subunit | Type | Name |

| ? | ? | CL | Yubari |

| ? | CruDiv 18 | OCL | Tatsuta |

| OCL | Tenryu | ||

| 6th DesRon | DesDiv 29 | DD | Oite |

| DD | Mutsuki | ||

| DD | Yanagi | ||

| DD | Oboro | ||

| DesDiv 30 | DD | Yayoi | |

| DD | Mochizuki | ||

| DD | Asanagi | ||

| AM | Kiyokawa | ||

| AE | Tsugaru | ||

| ? | ? | APD | Patrol Boat |

| N ° 32 | |||

| ? | ? | APD | Patrol Boat |

| N° 33 | |||

| ? | XAP | Tenyo Maru | |

| ? | ? | XAP | Kongo Maru |

| ? | ? | XAP | Konryu Maru |

| 4th Fleet | CruDiv 8 | C | Tone |

| C | Chikuma | ||

| CruDiv 6 | C | Aoba | |

| C | Furataka | ||

| C | Kako | ||

| C | Kinusaga | ||

| 2nd Fleet | CarDiv 2 | CV | Soryu |

| CV | Hiryu | ||

| C | ? | ||

| C | ? | ||

| DesDiv 17 | DD | Tamakaze | |

| DD | Unakaze |

It

is a matter of conjecture whether the relief operation would have been

successful, or whether fleet losses would have been substantial.

[31]

It should be noted, though, that two other

carrier groups had also been dispatched

[32]

and

could have provided air support in case of a confrontation with Japanese forces.

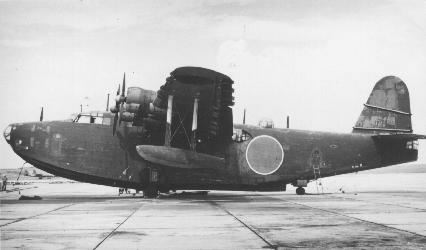

Figure 4. A Japanese Kawanishi H8K 'Emily" Flying Boat in Ebeye during World War II. Such aircraft were used for reconnaissance as well as long range bombing runs.

The second assault The second Japanese assault on Wake Island occurred in the night from the 22nd to 23rd December. [33] The Japanese expected about 1000 troops and some 600 civilian labourers to be present on the island. [34] As in some nights before, the Japanese vessels created a diversionary display of gun fire, lights and rockets north of the atoll. [35] A second naval force with the landing party managed to come very close inshore and to erect a beach head on the southern shore almost undetected. This time round, however, the Japanese took no chances. The amphibious task force consisted of 17 vessels, again under the command of Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajoka, flying his flag from the light cruiser Yubari. The losses of the original fleet had been replaced, and the fleet been strengthened by the addition of yet another destroyer, a sea-plane tender, a mine-layer and another transport (table 4).

In addition, however, there was a support group consisting of four heavy cruisers, among them the Tone and the Chikuma, with a screen of accompanying destroyers detached from the 4th Fleet at Truk. [36] A second support group comprising two aircraft carriers, Hiryu and Soryu, two cruisers and a destroyer screen, [37] had been detached from the task force which had carried out the attack against Pearl Harbor and had been returning to Japanese waters, having prevented by weather from making a scheduled strike against Midway. [38]

Two old Japanese destroyers converted into transports (the patrol boats No. 32 and 33) were run aground at the southern shore of Wake Island and men were landed from both. In addition, landings by barges and landing craft occurred at the ocean sides Wilkes and Peale and even in the inner lagoon, having entered it on rubber boats coming from the north-west across the reef flat. Rather than relying entirely on the 450 assault troops from Kwajalein and the other Marshall Islands bases, Admiral Kajioka was given the 2d Special Naval Landing Force, about 1000 men under command of Commander Maizuru, which had been sent over from Saipan.

Surrender The landing force consisted as a core unit of the Maizuru 2nd Special Naval landing Force (SNLF). The Japanese landing operations began at 2:50 and by 7:30, after fierce but apparently confused fighting, the Wake Island garrison had surrendered. As a result of the surrender, the Japanese came into possession of some classified information, which facilitated a bombing raid on Pearl Harbor on 4 March 1942, which had been staged through the French Frigate Shoals. [39]

Casualties Despite the continued bombing and the hand-to-hand combat which developed during the final capture, the losses on Wake were moderate. In total, during the defense of Wake the U.S. garrison lost 51 Navy personnel and between 33 and 80 civilians. [40] Another 50 were wounded.

Table

5. U.S. casualties on Wake (December 8-23, 1941)

[41]

| Casualty Level | ||||

| Service | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total |

| l | ||||

| Marines Officers | 5 | 6 | 0 | 11 |

| Marines Enlisted Men | 42 | 26 | 2 | 70 |

| Navy Officers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Navy Enlisted Men | 3 | 5 | 0 | 8 |

| Civilians | 70 | 12 | 0 | 82 |

| Total | 120 | 49 | 2 | 171 |

The

Japanese casualties are not known exactly, but are substantially higher. On two

incidents alone, at least 500, but possibly as many as 800 people drowned when

the destroyers Hayate and Kisaragi were sunk

[42]

and some 100 soldiers were killed by gunfire

during the second, successful, assault on Wake.

[43]

Table

6. Estimated Japanese Navy casualties on Wake (December 8-23, 1941)

[44]

| Casualty Level | |||||

| Service | Type of loss | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total |

| Airwing | carrier planes | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Airwing | landbased bombers | 80 | 0 | 0 | 80 |

| Airwing | reconn. planes | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Landing force | Destroyers | 500 | 0 | 0 | 500 |

| Landing force | vessels | 80 | 160 | 0 | 240 |

| Support force | submarine | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| Invasion force | ground troops | 125 | 125 | 0 | 250 |

| Invasion force | landing craft | 7 | 25 | 0 | 32 |

| Invasion force | destroyer | 5 | 10 | 0 | 15 |

| Total (approximate) | 843 | 320 | ? | 1167 | |

Table

7. U.S. equipment losses (December 8-23, 1941)

[45]

| Category | Class | Type | N° |

| Aircraft | Fighter planes | Grumman F4F-3 "Wildcat" | 12 |

| Guns | Coastal defense guns | 5" World War I vintage | 6 |

| Guns | Anti-aircraft guns | 3" | 12 |

| Guns | Machine-guns | 0.50 cal. | 24 |

Table

8. Estimated Japanese equipment losses (December 8-23, 1941)

[46]

| Category | Class | Type | N° |

| Aircraft | carrier attack planes | Mitsubishi A6M "Zero"(?) | 4 |

| Reconnaissance planes | Kawanishi H6K "Mavis" | 1 | |

| Land-based bombers | Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" | 16 | |

| Ships | Destroyer | DD Hayate | 1 |

| Destroyer | DD Kasiragi | 1 | |

| Submarine | RO-62 | 1 |

Deportation Unlike other civilians caught by the Japanese, such as Embassy personnel, the civilian CPNAB contractors were not afforded the possibility of exchange. Because the contractors had been naval bases and because several of them had been taking up arms in order to fend off the invasion, the Japanese considered them to be prisoners of war. On January 12th, 1942, the U.S. garrison of Wake, as well as a large contingent of civilians was transported from Wake Islands on board of the Japanese passenger ship Nitta Maru.47 The PoW's were brought to Japan and then China and housed in various PoW camps, where a large number of people died. [48]

A total of 346 civilian contractors was retained to work for the Japanese, to operate the machinery and to develop the Japanese defense system. One civilian was beheaded on mother's day 1942 to set an example for the others; [49] one civilian died [50] and two others set out in a stolen boat and perished at sea. [51] The fortification of Wake Atoll began in earnest in August 1942 [52] and night soil was shipped in from Japan in order to improve the poor atoll soil. The defenses apparently largely complete, all but 98 civilian workers were relocated to Japan on 30 September 1942 board of the Tachibana Maru for internment in Japan or Japanese-held China. [53]

Fearing a U.S. landing in late 1943, the Japanese executed 98 civilians on October 7, 1943 [54] after the bulk of the U.S. carrier strike against Wake Island of 5-6 October. [55] The Japanese feared a massive U.S. landing, in response of which part of the 4th Fleet in Truk was moved towards Wake.

Figure 5. Organisational structure of the Japanese Forces in Marshall and Gilbert Islands before the outbreak of the Pacific War

Command structure of the Japanese forces in the Marshall and Gilbert Islands After the outbreak of the Pacific War, the Japanese occupied the British Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati) and set up a small base on Makin, which was subordinate in command to the 51st Naval Garrison Unit on Jaluit. In addition, the occupation of Wake Island led to the establishment of an additional Naval Garrison Unit there, the 54th Keibitai, which was considered to be more important and thus was made directly subordinate to the 6th Base Force on Kwajalein (figure 6).

Following the U.S. submarine raid on Makin under the command of Colonel Carlsson on August 17th, 1942, the inadequacy of the Japanese defenses in the Gilberts was laid wide open. In response, the Japanese 4th Fleet headquarters immediately set up a defense command to occupy and defend the remaining Gilbert Islands as well as Ocean Island and Nauru. The command on Tarawa, Makin and Apemana was directly subordinate to the 6th Base Force on Kwajalein, while the occupation forces on Ocean Island and Nauru were made subordinate to the Guard Units of Jaluit and Kwajalein respectively (figure 6).

It appears likely that the decision to develop Mile into full base, was reached by about the same time, probably in response to the altered situation in the Gilberts and in response to some strategic problems in the western Marshalls. At the same time, it appears, the development of the seaplane base on Djarrit Island, Majuro Atoll, was halted. reasons for this halt seem to have been the overall shortness of construction materials and crews, and the new strategic situation which did not call for operating two two bases (Majuro and Mile) in close vicinity to each other.

On February 15th, 1943, the Gilbert Islands defense command was upgraded to an independent command, the 3rd Special Base Force, established on the same echelon level as the 6th Base Force itself. This upgrading clearly indicates the strategic importance the Japanese High Command gave the Gilbert islands in the overall defense strategy (figure 8.). Under the same restructuring, a separate Guard Force command, the 66th Keibitai was set up for Mile Atoll.

The successful seizure of the Gilbert Islands by U.S. forces in December 1943, made necessary the reorganisation of the remaining bases previously under the command of the 3rd Special Base Force in Tarawa. Rather than re-allocating Ocean Island and Nauru under the Guard Units of Jaluit and Kwajalein, as had been the case in late 1942, the two bases were set directly under the command of the 6th Base Force (figure 9). Furthermore, the detachment of the 61st Guard Force on Enewetak was upgraded to a full Guard Force status as the 68th Keibitai, thereby shortening the line of command and giving Enewetak more administrative independence.

The fall of Kwajalein and Enewetak the headquarters of the 6th Base Force was removed to Truk and the Guard Forces on the remaining atolls bypassed by the American troops, Jaluit, Wotje, Maloelap, Wake, Mile and Nauru, were directly answerable to the headquarters of the Combined Fleet in Truk and later in Tokyo (figure 9).

Role of Wake Island in the strategic defense of the Marshall and Gilbert Islands Once Wake had fallen, the Japanese were in the position to launch attacks on U.S. bases on Midway and Johnston Atolls, thus effectively curtailing the U.S. Navy's activity in the area. Wake was immediately and fully integrated into the Japanese defense system of the Gilbert-Marshalls area. Along with the airbases on Kwajalein, Wotje and Jaluit, as well as Marcus Island, Wake had become a base to launch long-range sector patrols. The Japanese defensive perimeter had been substantially widened and strengthened.

In keeping with this, the Japanese base on Wake carried mainly long-range patrol bombers, both land-based "Bettys", "Nells" and "Sallys" as well as flying boats. [56] For the defense, a squadron of fighter planes had been stationed there. [57] The air wing stationed on Wake belonged to the 22nd and later the 24th Air Flotilla of the Japanese Navy, headquartered on Roi. The Japanese Army apparently never operated aircraft in the area. [58]

Following increased U.S. attacks on the Japanese positions in the Gilbert Islands, the Japanese 4th Fleet Headquarters in Truk activated a defense plan for the Gilberts, Operation Hei.

"[G]ist of of principal operation orders, plans ... [and] directives for the defense of the Marshall Islands :

(2) Dispose air strength in depth and concentrate air attack strength at rear bases. By doing this it will obviate being surprised even though information gained from patrols is scanty. Plan to use bases at Enewetak and Wake as much as possible." (USSBS 1946a:199)

Wake also had limited naval base operations. A bombing attack on 15 May 1943 identified three Japanese destroyers [59] in the lagoon in the process of moving out through the channel. [60] To aid the defense of Wake against landing attempts, 4 patrol boats were transferred to Wake. [61]

Japanese installations on Wake On December 22nd, 1941, a day before the landing, the Japanese renamed Wake Island into Ottori Jima.[62] According to Scott Cunningham, Commander of the U.S. Forces on Wake until surrender in December 1941, the Japanese were busy installing new guns soon after they had landed, and several guns were in position, emplaced and tested even before the U.S. prisoners of war had been taken off the island on January 12th, 1942. [63]

In the following months the Japanese heavily fortified Wake island, the main development taking part after August 1942. [64] Since the Japanese feared a retaliatory landing on Wake, the defense system of the atoll had been excessively developed, more so than on most of the Marshall Islands bases.

Coastal defenses: With the help of the captured American heavy earthmoving machinery the Japanese continued the development of the Wake Air base. To prevent armoured landings the degree possible, all islands were provided on their entire oceanward periphery with huge anti-tank ditches, the fill being heaped on the landward side of the ditch in a manner resembling prehistoric fortifications. A similar ditch was dug on the lagoonward side of Peale island, and several other tank traps were dug transversely across the main islets, destined to impeded the progress of any enemy successfully landed.

Seaward of the tank traps was a system of personnel trenches, rifle pits and concrete, coral and steel pillboxes. The beaches had been liberally covered with barbed-wire entanglements and land mines. At a later point when the barbed wire had rusted away pointed ends of shrubs were set into the sand at an angle pointing seawards.

Inland defenses: Inshore of the tank traps was a network of defensive systems, consisting of over 200 coral and concrete pillboxes, blockhouses, 2 concrete fire control centres for the AA searchlights, 8 concrete magazines, seven of which were of American origin, 25 bombproof shelters and 15 command posts.

Guns: The guns available for the defense of Wake consisted of an odd assortment of weaponry from a number of sources. [65] Emplaced on the three islets were in total 120 guns and heavy machine guns (table 9), ranging from 8" coastal defense guns taken from old World War I vintage warships to 36 Army field artillery pieces (75mm and 37 mm) and 24 light tanks with 37mm cannons.

All gun emplacements had been set in proper revetments of coral boulders and sand. The mobile artillery had been emplaced individually in revetments.

Table

9. The Japanese defense system. Field artillery and guns emplaced on Wake.

[66]

| Type | Purpose | N° | Emplaced on/at | Origin |

| 200mm | Coastal Defense | 4 | Wake & Peale | old Japanese Naval guns |

| 150mm | Coastal Defense | 4 | Wake & Peale | old Japanese Naval guns |

| 127mm | Dual Purpose twin mount | 8 | Wake & Wilkes | new Japanese Naval gun |

| 80mm | Anti aircraft | 4 | Peacock Point | new Japanese Naval guns |

| 80mm | Dual purpose | 1 | Peale | |

| 5inch | Dual Purpose | 6 | Wake | Captured U.S. guns |

| 3inch | Anti-aircraft | 9 | Wake, Peale & Wilkes | Captured U.S. guns |

| 25mm | Machine guns twin mount | 24 | Wake & Peale | new Japanese Naval guns |

| 37mm | Field artillery | 12? | mobile | new Japanese Army guns |

| 75mm | Field artillery | 24? | mobile | new Japanese Army guns |

| 37mm | Light Tanks | 24 | mobile | new Japanese Army tanks |

Command buildings: All buildings were heaped with coral and sand to eliminate shadows and provide concealment, which was greatly enhanced by shrubs planted on them (figure 16). The hospital was also set up under ground.

Air establishment: Large-scale aircraft revetments were build at the intersection of the runways and smaller ones were constructed along the southern margin of the E-W running main strip. Despite these, a number of aircraft was destroyed on the ground.

The airfield, when completed, had three runways, the main runway ("A"), running East-West with a length of 5,500 feet, another bomber strip ("B") running northeast-southwest for 4,870 feet, and shorter fighter strip ("C") running north-south for 1,680 feet.

Barracks: The main barracks area was located there where the Americans had theirs, in the northwestern part of Wake and on the southwestern arm of Wake and on adjacent Wilkes.

All buildings were placed just above the water table in revetments, guarding them against attack save for direct hits.

Supplies and machinery: The petroleum products had been placed in blockhouses or buried in sand, 10 to 16 drums to a heap. Trucks, jeeps and tanks had their own little revetments.

The base also operated two radar sets, one on top of the old PAA station and one on the ruins of the US contractors Camp. The Japanese had erected a multiple RDF facility on the northern arm of Wake Island. The facility consisted of three wooden three-storey buildings, similar to those observed elsewhere. [67]

Extension of the base facilities As had been mentioned earlier on, the U.S. had intended to utilise Wake also as a submarine base. To that end the U.S. engineers and civilian contractors had begun to dredge a completely new channel through the centre of Wilkes. [68] The dredging of the channel continued under Japanese supervision using the U.S. civilian prisoners of war. It finally came to a halt when the dredge Columbia was hit in Wake lagoon by naval gunfire from the cruisers U.S.S.Northampton and U.S.S. Salt Lake City during the U.S. carrier raid of 24 February 1942. [69]

Strength of the Japanese Garrison The build-up of the Japanese defense system on Wake occurred gradually as far as deployment of troops was concerned. The Japanese defense forces stationed on Wake were the 65th Naval Guard Unit, supplemented by the 2nd Battalion of the 170th Infantry Brigade, which had seen action in New Guinea. In addition, there was part of the 4th Naval Pioneer Battalion of about 1000 men and parts of the 22nd and later the 24thAir Flotilla (Koku Sentai).

The troop strength of the Wake Atoll garrison was approximately 2700 men by December 1942 and 3100 men in early 1943. Anticipating an U.S. attack it was augmented with 1000 Army troops to a total of 4100 men in January 1944. Of these some 600 died as the result of enemy activity and about 1300 as a result of starvation and disease.

In January 1944 the Japanese had stationed 2,050 Army troops of Wake. [70]

Command of Wake The Japanese garrison on Wake Atoll was under the command of Admiral Kajioka, the commander of the amphibious task force attacking and capturing Wake.

In January 1942 Captain Sususmu Kawasaki, IJN, was appointed island/atoll commander. He oversaw the construction of the Japanese defenses. Upon completion of most of the construction, he was relieved on 13 December 1942 by Captain Shigematsu Sakaibara, IJN. [71] Sakaibara stayed in command until the surrender of the garrison. Sakaibara's executive officer was Lieutenant-Commander Soichi Tachibara, IJN. The commander of the Army forces, Colonel Shigeharu Chicabari, IJA, was subordinate to the executive officer.

The chain of command for the Wake garrison after its establishment as an independent command in January is given in table 10. While the atoll commander and CO of the 65th Keibitai had the authority of integrating command over both the naval and the army garrison troops, his command did not extent to the navy air wing stationed on Wake:

"The Naval Commandant (Commander in Chief, 4th Fleet) was responsible for the integration of command.

The senior commandant exercised the authority of integrating command in their respective islands. However, as far as air operations were concerned, the air forces took direct orders from Combined 22nd Air Squadron; while only in case of co-operating with defensive operations on land, were they subjected to integration of command by the Senior Commandant present on the spot." [72]

Table 10 Hierarchy and officers in command for the Wake garrison in November 1943 [73]

Supplies Before the arrival of U.S. forces in Marshallese waters, the Japanese garrisons on the various atolls were commonly supplied directly from Japan once every six months with major food supplies and staples. [74] Truk Ponape Small supplies, were delivered at least monthly from the main base at Kwajalein by motorlaunch. Mail was delivered by transport planes or flying boats, either from Kwajalein or directly from Truk. [75]

Table

11. Typical assortment of Japanese food supplies in overseas garrisons.

[76]

| Drinks: | Fruits and vegetables: |

| Green tea in tin layered boxes | Boiled bamboo sprouts in cans |

| Powdered milk in cans | Fried bean curd |

| Sweet sake in cans and bottles | Boiled burdock in cans |

| Cider in bottles | Apple (dehydrated) |

| Beer in bottles | Boiled loyus rhizome in gallon cans |

| Gin in bottles | Sprouted beans |

| Karupis in bottles1) | Past of arum root in cans |

| Sea food: | Dried pumpkin in boxes |

| Sardines in cans | Boiled spinach in cans |

| Clams in cans | Mushroom in cans |

| 3-in-1: Clams, seaweed and beans | Bean flour in cans |

| Rolled seaweed (seasoned) in cans | Soy bean sauce in woo barrels or in cans.3) |

| Laver in dried form and seasoned | Soy bean paste in wood barrels |

| Mackerel in cans | Fruits and vegetables: |

| Salted salmon in cans | Mushroom in cans |

| Dried cuttlefish | Boiled bamboo sprouts in cans |

| Trout in cans | Fried bean curd |

| Dried Bonito Fish2) | Boiled burdock in cans |

| Cereals and staples: | Apple (dehydrated) |

| Rice in sacks and cans (>100 lbs) | Boiled loyus rhizome in gallon cans |

| Wheat in sacks (>100 lbs) | Sprouted beans |

| Rice cakes in cans | Past of arum root in cans |

| Powdered rice dumplings in cans | Dried pumpkin in boxes |

| Rice boiled together with red beans in cans | Boiled spinach in cans |

| Biscuits | Bean flour in cans |

| Wheat gluten in cans | Soy bean sauce in woo barrels or in cans.3) |

| Soy bean paste in wood barrels | |

| Special: | |

| Glucose in tablet form | Curry powder in cans |

| Vitamin pills | Sugar in sacks |

| Vinegar in bottles | Ginger |

| Beef (both seasoned and unseasoned) in | Essence of taste (of vegetable origin) |

| cans | in tin cans |

| Dried whole meat | Vitamin biscuits |

| Caramel | |

|

Notes: 1) A soft drink made from citric fruit derivatives and lactose;

2) Dried Bonito had been one of the main export products from the

Marshall Islands before the war; 3) Also dehydrated forms of sauce

in gallon-sized drums.

| |

There was a daily ferry service by transport plane of mail and personnel

between Wake and Kwajalein. The bulk of the supplies for Wake arrived via

Kwajalein Atoll, the headquarters of the 6th Base Force. Here, at

Roi, the Japanese operated a large pier facility capable of handling large

amounts of goods. The unloading and transshipment of even heavy goods, such as

guns, was facillitated by a large hammerhead crane, capable of lifting about 40

tons. [77]

Smaller boats provided the

transshipment of goods from Kwajalein to Wake.

U.S. planes attacking the atoll regularly reported the presence of merchant and naval units, both off Wake and in the lagoon. End of January 1943 two small cargo ships were seen south of the southern channel entrance, a small boat in the harbour, two small vessels off Toki Point in the lagoon and two merchant vessels south of the channel entrance. [78]

All Japanese garrisons had sufficient food stores to last for a period of six months or more. The supplies consisted of rice, barley, canned foods, such as beef, bamboo sprouts, and fruit, biscuits, beer, saki and cigarettes. Since nothing was left of the food stocks of Wake after surrender, and since the documentation/archives of the 65th Keibitai have been destroyed before surrender, we do not have any detailed account of what had been supplied to Wake. While the variety of Japanese building and clothing supplies provided to the individual garrisons would vary according to the type and geographical location of the base, the variety of food supplies is unlikely to vary substantially - if at all.

In conjunction with the attempted landing on Midway in mid-1942, the Japanese undertook successful landings in the Aleutians, Alaska, and established bases there. One of these bases was evacuated peacefully and orderly, and from the U.S. accounts of what they found there we have a fairly complete list of food supplies sent to Japanese garrisons overseas (table 11).

The submarine offensive of the U.S. Navy in the waters of the Marshall Islands [79] was stepped up in August 1943 and was cancelled in the Marshall Islands when airborne warfare could be executed out of Majuro and Kwajalein [80] During this time, and especially after the fall of the Japanese bases in Kiribati, when U.S. daylight attacks on Japanese inter-atoll shipping had become so common that Japanese vessels transporting supplies apparently moved only at night, hiding close to islands during the day. The dominance of U.S. air power in the Marshall islands after January 1944 meant that supplies could no longer be shipped to the garrisons.

The last supply vessel to come through to Wake was the Akagi Maru, which reached Wake in January 1944. The same vessel apparently made two further unsuccessful attempts to break the U.S. blockade. Thereafter, it seems, Wake was successfully supplied by submarines, which arrived at monthly of six-weekly intervals. The last submarine to reach Wake arrived on 28 June 1945. [81] The submarines brought mail, medical supplies and small stocks of food and ammunition. The food supplies were insufficient to support the entire garrison, but were large enough to stave off the disaster which befell the Japanese garrisons on the southern bypassed atolls of Mile, Wotje or Maloelap.

Submarine food drops Once the U.S. attacks on surface shipping had been stepped up, and surface supplies no longer were a viable method, the Japanese attempted to supply their bases with rice, canned food, clothing and arms, but especially with new codebooks and the like by using submarines. The Japanese at least attempted several supply runs of the cut-off garrisons in the Marshall Islands area. [82] It is unclear how many submarines got through.

The losses of the Japanese submarine fleet in the beginning of 1944 were so considerable, eight boats [83] between February and June 1944, that the attempts were eventually abandoned, save for the resupply of the garrison on Wake Atoll, which continued until June 1945. [84] Each of these 2000 ton submarines dropped sufficient rice to supply 5,000 men for a period of 7 to 10 days. [85]

Water supplies As far as can be ascertained, the fresh and utility water supply of the Wake garrison relied on rainwater collection off the runways of the airfield and off the roofs of the barracks and other buildings. On other occasions, it appears, the Japanese seem to have brought in fresh water by water tanker ships from sources outside the Marshall Islands. [86]

U.S. Strategy regarding Wake "In the American Strategic Plan Wake was [once in Japanese hands] never regarded as an objective of major importance. ... Wake was always hardest hit when American operations were proceeding in adjacent areas, so that even the most important strikes against it were diversionary or protective in nature. For the rest, attacks on Wake were intermittent and of a harassing type." [87]

The total of the U.S. attacks on Wake was not known at the end of the war because a wide range of bombardment squadrons as well as a variety of services (army Air Force, U.S. Navy carrier groups, U.S. Navy shore-based groups and U.S.Marine Corps) had taken part in the attacks; while the mainstay of the early years were AAF B-24s operating from Midway, the land-based Navy patrol bombers took over in 1944 when bases in the Marshalls had been secured. [88] In addition to land-based bombardment, a number of carrier raids [89] as well as surface ship bombardments were carried out. [90] Attacks on Wake were commonly guarded by the deployment of submarines and sometimes destroyers to pick up the crew of downed aircraft if any. [91]

Carrier strikes against Wake The first carrier strike was carried out on 24 February 1942 by a task force centered on U.S.S. Enterprise, commanded by Rear Admiral "Bull" Halsey. [92] While this strike was largely for exercise as well as for a show of force towards the Japanese Navy, the next strike was destined to cripple Wake as a forward Japanese base.

In preparation of the U.S. landing in the Gilberts, to provide the carrier groups with combat training and in order to create a diversionary scene of battle, carrier raids were executed on Japanese bases in the Gilberts and Wake. The carrier strike on Wake was particularly heavy and carried out on 5 and 6 October 1943 by aircraft of Task Force 14, Rear Admiral A. E. Montgomery, flying a total of 738 combat sorties in six strikes. This task force, the largest ever assembled until then, comprised six aircraft carriers [93] and a defensive screen of cruisers [94] and destroyers, which also shelled the island.

22 Japanese planes, out of 65 claimed, were destroyed in the air and on the ground and shore installations were heavily damaged, with a U.S. losses totalling 12 aircraft in combat and another 14 operationally. [95]

In a reaction to this prolonged strike the Japanese command assumed that an all-out U.S. attack on Wake was in preparation and moved its combined 4th Fleet from Truk to Enewetak to be in striking distance intercepting any U.S. landing force. This anticipated naval battle, however, never eventuated as the U.S. attacked Tarawa and Makin in the Gilberts. [96]

Occasional carrier raids and naval shelling continued, the last carrier raids being executed on 13 August 1945, six weeks before the Japanese garrison on wake formally surrendered.

Land-based strikes against Wake On 23 December 1942 the first land-based night-bombing bombing mission flown by 26 B-24D planes of the 307th Bombardment Group (VIIth Bomber Command) from base on Midway documenting the feasibility of such missions. [97] ,

Between the above-mentioned carrier strike and the beginning of true land-based bomber attacks, the U.S. Navy sent two squadrons of Coronado flying boats from Midway to bomb Wake on January 29th, 1944. This was tenth of such attacks.

After the bloodless fall of Majuro Atoll on January 29th, 1944, the island of Delap was developed as an airfield with a 5800 foot runway, [98] from which attacks were flown against the Japanese bases in the Marshall Islands. [99]

After the successful landing on Kwajalein Atoll, both Kwajalein and Roi-Namur were developed into U.S. Naval air bases. The same happened on Enewetak. From these bases, then, land-based bombing raids and patrols could be flown over Wake either directly, or staged through Enewetak. A daily reconnaissance of Wake was flown from Enewetak. [100]

Figure 11. A Douglas SBD Dauntless over Wake

Naval shelling of Wake As a by-product of the carrier strikes against Wake the atoll was subjected to shelling by naval surface units, mainly cruisers, such as by U.S.S. Northampton and U.S.S. Salt Lake City on 24 February 1942, or by U.S.S. Minneapolis, U.S.S. San Francisco and U.S.S. New Orleans between 5 and 6 October 1943. [101]

The surrender of Wake On September 2nd, Japan surrendered in Tokyo Bay, and on September 7th, 1945, Wake was formally surrendered to the U.S.A. to Brig.Gen.Lawson Sanderson (USMC). The atoll is disarmed, all mobile weapons collected, land mines removed and ammunition caches destroyed.

On 1 November 1945 a large contingent of Japanese Prisoners of War is taken off Wake on board of the MS Hikawa Maru.

War crimes: the execution of the civilians 1943 As mentioned earlier, after the surrender of the U.S.garrison, a total of 346 civilian contractors was retained to work for the Japanese and to develop the Japanese defense system. One civilian was beheaded on mother's day 1942 to set an example for the others. [102]

Fearing a U.S. landing in late 1943, the Japanese executed the remaining 98 civilians PoW's on October 7, 1943 [103] after the bulk of the U.S. carrier strike against Wake Island on 5-6 October. [104] The Japanese feared a massive U.S. landing, in response of which part of the 4th Fleet in Truk was moved towards Wake.

On 5 November 1945 Rear Admiral Sakaibara and 15 of his officers were shipped to Kwajalein to await trial for war crimes committed on 7 October 1943 against 98 U.S. civilians. Two officers, who had admitted the fact and implicated the others committed suicide en route.[105] Tried and found guilty Sakaibara and his adjudant Lt.Cdr Soichi Tachibana were sentenced to hanging by the Military Commission. On 19 June 1947 Rear Admiral Sakaibara and Tachibana are executed.

This changing global picture also had its effects on the role of Wake in the U.S. strategic concept. The function of Wake Island has frequently shifted after World War II, increasingly loosing importance to the United States.

Administrative control over Wake Well before the end of the war, strategic plans for the post-war period were drawn up, and a base on Wake was once again contemplated. After the recapture of Wake the U.S. Navy once again had jurisdiction over the atoll. [106] While a major base was considered in the beginning, in the event, the plans were scaled down, Wake was to be kept merely to prevent its use by others, [107] and thus was developed into a smaller installation (see below). Both the State Department and the Department of the Interior vied for the administrative control over the atoll in the late 1940s. [108] Administration of Wake Atoll was in the hands of the United States Department of the Navy (except during the Japanese occupation) from 1934 to 1948, when jurisdiction over the islands was transferred to the Department of Commerce by act of Congress. The Department of the Navy retains the right to re-establish administrative control of the atoll in the event of any future emergency, but at present the administration is under the control of the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA). All legal matters on the islands are under the jurisdiction of the Federal Courts, specifically the United States District Court of Hawaii at Honolulu, since the entire atoll is government property. The legal machinery of Wake consists of a Deputy United States Marshal and a United States Commissioner, which are both part-time positions. Eventually, by 1950 the administration of Wake had been transferred from the U.S.Navy to the Interior Department and then to the United States Air Force. [109]

Land ownership Since the entire atoll is federal property, there is no private ownership of land. The Administrative Department of the Federal Aviation Agency issues land use permits, and also controls all real estate and rental units.

The original Pan American Airways concession on Peale Island which covered several acres and included shops, hangars, living quarters, a restaurant, and a hotel, was completely destroyed during the war, as were the various Marine and Naval installations built in 1940 and 1941. Later, the more numerous Japanese installations were also mostly destroyed during the numerous United States attacks on the islands. Most of the housing units and many of the major installations which were built between 1946 and 1952 were destroyed during the hurricane of 1952, when the estimated 180-mile-per-hour peak winds (the recording equipment broke at 163. 5 miles per hour) combined with the waves which covered much of Wake Island during the height of the storm to sweep away the majority of the island's smaller buildings. In general, then, the majority of the buildings now on Wake Atoll were built after September of 1952.

Wake Atoll is a designated National Defensive Sea Area and Air Space Reservation, and has been since 1941, except during the Japanese occupation. According to this directive the atoll is closed to the general public. No vessels or aircraft, except those authorized prior to arrival by the Secretary of the Navy or the Commanding Officer of the Hawaiian Sea Frontier, are permitted to pass in or above the area within the 3-mile limit surrounding the atoll. However, this restriction is mainly a technicality at present, since all types of commercial as well as military aircraft land at Wake Island airport daily. There is no longer any restriction on photography, nor is it necessary to be a United States citizen to land on Wake. However, special permission is still necessary for an individual to stay on Wake for more than the usual 50-minute meal stop. It seems that this latter restriction is due more to a shortage of supplies and hotel facilities than to the defense directive. Most of the major facilities as well as the housing are concentrated on Wake Island.

Wake Island Air Force Base As mentioned, at the end of World War II it was intended to develop Wake Island, along with Palmyra and Baker into a major base. In the event, the plans were scaled down and Wake was developed into a smaller installation (Richard 1957c: 26).

In the late 1950s there was only one runway in use on Wake Island. Running almost east-west, the runway had been extended to 9,500 feet in length, with an additional 1,000 feet of overrun length at the western end. It was more than 100 yards wide and was constructed of reinforced concrete on a base of crushed coral.

In 1976 the oil tanker R.C.Stoner, suppling aircraft gasoline and other fuel to Wake Atoll, foundered off the harbour entrance in September 1967, causing considerable pollution of marine life. [110]

Land use in the 1950s In the late 1950s the main commercial land use was the airport, which was operated by the FAA. The three main companies involved are Pan American Airways, Trans-Ocean Airlines, and the Standard Oil Company (which operates the refueling service and the tank farm). The Military Air Transport Service (MATS) was the largest single user of the Wake Island Airport, however. The western end of Wake Island was devoted to the docks and landing area, as well as to warehouse facilities. The western part of Wilkes Island was a bird sanctuary, while the center of the eastern end of the island has the Standard Oil tank farm (which was run by MidPac Operators, the Standard Oil operating agency in the Pacific).

In the late 1950s the lagoon was still in use as a seaplane landing base, although with the advent of long-range land-based planes in the late 1940's the use of seaplanes and amphibians has greatly diminished in the Pacific.

Wake and the trans-Pacific airroute (1950s) On 24 September 1946 Pan American Airways resumed operations through Wake and continued it until December 7, 1971.

In the 1950s Wake Island served as an stop over point on the Honolulu - Saipan route. As such it was utilised by Trans-Ocean Airlines, Philippine Airlines, PanAm and TWA. In 1952 Wake was largely devastated by typhoon Olive, but reconstruction and development began immediately afterwards,

In the mid-1950's, employees of Pan American Airways, Standard Oil and the U.S.Coast Guard were stationed on Wake Atoll. For these employees recreational facilities were erected, such as a golf course [111] and a flying club. [112]

The most important business on Wake Atoll was the refueling and maintenance of airplanes which use the facilities of the atoll while en route across the Pacific. Wake's distance from the United States made the supplying of fuel more expensive, and required a large storage capacity in the local tank farm, to permit operations to continue in the event of a temporary interruption in the delivery of fuel by tanker from Richmond, California.

Table

12. Air traffic volume on Wake in the calendar year 1959.

[113]

Commercial airlines which landed at Wake Island airport were Pan American Airways, Trans-Ocean Airlines, Flying Tiger Lines, Japan Air Ways, and the British Overseas Airline Corporation. The largest single user of Wake Island's facilities was the Military Air Transport Service, which sent as many flights through Wake as do all the private operations combined. Other military aircraft are also heavy users of the Wake Island airport. Figure 11 shows the relative frequency of the various types of aviation using Wake Island. It was said that over the years more than 3 million passengers have set foot on Wake. In 1959 there were a total of 27 weekly commercial airline flights carrying passengers which arrived at Wake.

Figure 11. Air traffic volume on Wake in the calendar year 1959.

With the advent of jet propelled aircraft, the need for a stop-over even on the long distance routes disappeared and Wake's role was relegated to that of an emergency air field and stop over place for planes too small to fly direct. [115] The settlement of Wake, both civilian and military had grown to such an extent that infra-structure needed to be provided, such as schools [116] and the like.

Apart from these, some minor installations existed on Wake. The extent of the current (1990) development is unclear as little sources are available.

Missile testing On Wilkes Island are the Pacific Missile Range missile-impact location systems (MILS) building and their cable connection to the mainland. [117]

Coast Guard Station Peale Island, besides housing a small detachment of Coast Guard personnel and their LORAN unit, has a number of housing units.

The Truman-McArthur summit 1950 In October 1950 was the location for a much publicised meeting between President Truman and General Douglas MacArthur to discuss the Korean situation and the overall U.S. strategy in the developing Cold War between with the U.S.S.R. and China. [118]

Wake in the 1960s Although the new airport terminal was completed in 1962, Wakes importance for trans-Pacific air traffic was over. The U.S.installations were continuously scaled down during the late 1960s. The U.S.Coast Guard operated a station on Peale until 1963(?).,

Temporary immigration camp 1975 Following the fall of Saigon at the end of the Vietnam war in 1975 some 15,000 Vietnamese refugees stayed at Wake Island for the duration of up to four months, while awaiting transportation and relocation to the U.S.A. [119]

Resettlement of the Bikini people 1979 In September 1979 a delegation of Bikini people visited Wake Atoll in order to assess its suitability for resettlement in lieu of Bikini Atoll. [120]

Wake as a depository for low-level nuclear waste Following the accident of the nuclear power station on Three Mile Island near Harrisburg, Va., Wake was for a short time touted as a potential depository for the low level radioactive waste resulting from the clean-up. [121]

In the late 1950s and early 1960s Wake Island was seen as a secondary, but vital base, a naval airfield guarding the approach to Hawaii. [122] This assessment gradually changed, possibly in the conjunction with the ever faster development of nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles. It appears that in the early 1970s, then, Wake was no longer considered vital for the defense of the U.S.A., [123] although still considered useful. [124]

More importantly, though, was that the use of such small islands be denied to other nations, possibly hostile to the U.S.:

"... a number of very small islands with no permanent inhabitants (eg. Midway, Wake) also serve America's military needs. Technological developments, economic crises and political reappraisals lead to frequent changes in appreciations of strategic requirements, but it can be assumed that the United States will at least continue to attach importance to denying politically hostile foreign powers access to such facilities. The significance of this factor is clear when one considers the future of America's Pacific dependencies" [125]

On the other hand, as the Gulf Crisis has shown, conventional warfare can erupt in other places of the globe, necessitating the relay of large amounts of troops and war materiel in short time. In addition, advanced operational bases for the operation of jet aircraft, ranging from medium- and long-range bombers to fighter planes are needed.

Abo, T., B.W.Bender, A.Capelle & T.DeBrum, 1976, Marshallese-English Dictionary. PALI language Texts: Micronesia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Amerson, B.J., 1971, The Natural History of French Frigate Shoals, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Atoll Research Bulletin 150. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Angelucci, E. & P. Matricardi, 1977, World War Airplanes. Vol. II. Chicago: Rand McNally & Co.

Ayres, P.A., 1940, Wake - the vegetable isle. Paradise in the Pacific 52 (1):13 [January 1940].

Carter, J., 1986, The Pacific Islands Year Book. 15th edition. Sydney: Pacific Publications.

Carter, K.C & R.Mueller, 1973, The Army Air Force in World War II. Combat Chronology 1941-1945. Washington: Albert Simpson Historical Center, Air University & Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF.

Cohen, S., 1983, Enemy on island - issue in doubt: the capture of Wake Island, December 1941. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co.

Craven, W.F. & J.C.Kate, 1950, The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. 4: The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan August 1942 to July 1944. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Crowl, P.A. & E.G.Lowe, 1955, Seizure of the Gilberts and the Marshalls. The War in the Pacific. United States Army in World War II. Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army.

Cunningham, W.S., 1961, Wake Island Command. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Devereux, J.P.S., 1947, The story of Wake Island. Philadelphia, New York: Lippincott Co.

Drummond-Hay, Lady Hay, 1939, A trip to Wake Island. China Journal 30, 333-339.

Esmond, T.M., 1943, Report on Mission performed by Lt.T.M.Esmond and crew, flying B-24D 41-23956. Annex No. 3 to Consolidated Mission Report. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

Fueta, K., 1947, Evidence given during interrogation. In: USSBS 1947a, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The American campaign against Wotje, Maloelap, Mille and Jaluit. Washington: Naval Analysis Section, United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Pp. 225-232.

HAAF, 1942, Headquarters Army Air Forces, Wake Island Group, Photo Intelligence Report No. 62. Director of Intelligence Service, Headquarters Army Air Forces. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

Hashimoto, M., 1954, Sunk: The story of the Japanese Submarine Fleet 1941-1945. New York: H.Holt & Co.

Heine, C., 1974, Micronesia at the Crossroads. A reappraisal of the Micronesian Political Dilemma. Honolulu: East-West Center, University Press of Hawaii.

Heine, D., & J.A.Anderson, 1971, Enen-kio Island of the kio flower. Micronesian Reporter 14 (4), 34-37.

Heinl, R.D., 1946, "We're headed for Wake". Marine Corps Gazette June 1946.

Hough, F.O., V.E.Ludwig & H.E.Shaw, 1958, History of U.S. Marine Corps operations in World War II. Volume I: Pearl Harbur to Guadalcanal.Washington, D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, U.S.Marine Corps.

ICPOA, 1942, Comprehensive Report Photographic Intelligence Report No. 33. Sortie Army-3, July 31. 1942. Dated August 6, 1942. Photographic Reconniassance and Intelligence Section, Intelligence Center Pacific Ocean Areas. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

ICPOA, 1943, Air Target Bulletin No. 14. Wake. 1 April 1943. ICPOA Bulletin No. 27-43. Intelligence Center Pacific Ocean Areas. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

IO371, 1943, Intelligence Officer, 371 st Bombardment Group, Mission report on Wake Island. 18 May 1943. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

IO372, 1943, Intelligence Officer, 371 st Bombardment Group, Mission report on Wake Island. 18 May 1943. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

Jentschura, H., D.Jung & P.Michel, 1977, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1869-1945. London: Arms & Armour Press.

JICPOA, 1944, Joint Intelligence Center Pacific Ocean Areas, Air Target and Photos ATF No. 23-A Wake. February 20, 1944. 64th Engr. Top. Co. USAFICPA No. 596-3.

Junghans, no date, The story of Wake Island. 32pp. illustrated. Ms. on file. Hamilton Library. University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Kephart, R., 1950, Wake, war and waiting. New York:Exposition Press.

Kitajima, 1947, Evidence given during interrogation. In: USSBS 1947a, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The American campaign against Wotje, Maloelap, Mille and Jaluit. Washington: Naval Analysis Section, United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Pp. P. 59.

Landon, T.H., 1943, Bombardment Mission Wake Island, 15 May 1943. Headquarters of the VII Bomber Command. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

Lee, G., 1980, Men and Island Matched, Isolated and Detached. New York Times 25 July 1980, Page 25.

May, C.P., 1973, Oceania, Polynesia, Melanesia, Micronesia. New York: Thomas Nelson Inc.

McHenry, D.F., 1975, Micronesia: Trust Betrayed. Altruism versus Self-interest in American Foreign Policy. New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

MIS, 1942, Military Intelligence Service, War Department Study of Wake. Text and Maps. Prepared under the direction of the Chief of Staff by the Military Intelligence service, War Department, June 15, 1942. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

Miwa, Shigoshi, 1945, Vice Admiral, C-in-C 6 th (Submarine) Fleet, Evidence given during Interrogation. USSBS Interrogation No. 366, Naval Interrogation No. 72. Date: 10 September 1945. U.S. National Archives RG 243 2 o (29).

Moore, J.W., 1943, Mission Report, Photographic Reconnaissance Wake Island 25 January 1943. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

Morison, S.E., 1948, History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. III: The rising sun in the Pacific. 1931-April 1942. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Morrison, S.E., 1951, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol VII: Aleutians, Gilberts & Marshalls.June 1942-April 1944. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Oishi, C., 1947, Evidence given during interrogation. In: USSBS 1947a, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The American campaign against Wotje, Maloelap, Mille and Jaluit. Washington: naval Analysis Section, United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Pp. 209-215.

Ramey, H.K., 1943, Raid on Wake Island, December 23, 1942. Special Informational Intelligence Report No. 43-3. 27 February 1943. Intelligence Service, U.S. Army Air Forces, Headquarters of the VII Bomber Command. Contained in U.S.National Archives, Record Group 165, Records of the War Department, General and Special Staffs, Military Intelligence Division, "Regional File" 1922-1944, Box 1928 Islands, "Virgin-Windward" held at the Washington National Record Center at Suitland, Md.

Richard, D.E., 1957a, The United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 1: The Wartime Military Government Period 1942-1945. Washington, DC: U.S. General Printing Office.

Richard, D.E., 1957b, The United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 2: The Post-war Military Government Era 1945-1947.. Washington, DC: U.S. General Printing Office.

Richard, D.E., 1957c, The United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 3: The Trusteeshoip Period 1947-1951.. Washington, DC: U.S. General Printing Office.

Robson, R.W., 1945, The Pacific Islands Handbook 1944. North American Edition. New York: Macmillan Co.

SDB, 1952, Second Demobilisation Bureau, Inner South Seas Islands Area Naval operations. Part I: Gilbert islands operations. Japanese Monograph No.161, Headquarters Far East Command, Military History Section, Japanese Research Division. In: D.S.Detwiler & Ch.B.Bardick (eds.), War in Asia and the Pacific 1937-1949. Volume 5: The Naval Armament program and Naval Operations (Part II). New York: Garland Publishing Co.(1980).

Sherrod, R., 1952, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II. Washington: Combat Forces Press.

Smith, S.A. de, 1970, Microstates and Micronesia. Problems of America's Pacific Islands and other minute territories. New York: New York University Press.

Tomita, R., 1947, Evidence given during interrogation. In: USSBS 1947a, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The American campaign against Wotje, Maloelap, Mille and Jaluit. Washington: naval Analysis Section, United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Pp. 215-225.

United States, Congress, 1939, An act to authorise the Secretary of the Navy to proceed with the construction of certain public works, and for other purposes. April 25, 1939. House Resolution 4278. In: United States Statutes at large containing the laws and concurrent resolutions enacted during the first session of the seventy-sixth congress of the United Atates of America 1939 treaties, international agreements other than treaties, proclamations, and reorganisation plans compiled, edited, indexed, and published by authority or law under the direction of the Secretary of State Volume 53 Part 1 Public laws and reorganization plans Washington: United States Government Printing Office Pp.590-592.

United States, House of Representatives, 1957, Application of Public Law 815 (81st Congress) to Wake Island. Report from Committee on Education and Labor to accompany H.R. 7540. June 14, 1957. House reports on Public Bills No. 570, 85th Congress.

United States, Senate, 1957, Application of Public Law 815 (81st Congress) to Wake island. Report from Committee on Labor and Public Welfare to accompany H.R. 7540. July 30, 1957. Senate reports on Public Bills No. 766, 85th Congress.

USSBS 1946a, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The Campaigns of the Pacific War. Washington: Naval Analysis Division, United States Strategic Bombing Survey.

USSBS 1947a, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The American campaign against Wotje, Maloelap, Mille and Jaluit. Washington: Naval Analysis Section, United States Strategic Bombing Survey.

USSBS 1947b, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The rediiuction of Wake Island. Washington: Naval Analysis Section, United States Strategic Bombing Survey.

Verbeck, W.J., 1943 (?), The enemy on Kiska. U.S. Naval Intelligence, Section G-2.

Wiens, H.J., 1962, Pacific Isands Bastions of the U.S. Princeton, N.J.: D.van Nordstrand & Co.

Yanaihara, T., 1940, Pacific Islands under Japanese Mandate. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Yoshimi, N., 1947, Evidence given during interrogation. In: USSBS 1947a, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The American campaign against Wotje, Maloelap, Mille and Jaluit. Washington: Naval Analysis Section, United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Pp. 54-57.

19 August 1941 An advance party of the 1 st Marine Defense Battalion arrives and makes camp

15 October 1941 Major J.P.S.Devereux arrives and takes command as island commander and marine detachment commander.

2 November 1941 200 U.S. Marines arrive as reinforcement from U.S.S.Castor

29 November 1941 Commander W.S.Cunningham arrives and relieves Devereux of his duty as island commander

VMF-211 advance party arrives and commences preparations for the operations of airbase

3 November 1941 Aerial photography of Wake by planes of Patrol Wing 2.

3 December 1941 Japanese Naval Attack force arrives at Roi, Kwajalein Atoll, from Truk, headquarters of the 4 th fleet

4 December 1941 VMF-211 flies to Wake from U.S.S.Enterprise

8 December 1941 Last scheduled Pan American Airways flight from Honolulu to Guam, returns to Midway after news of the Pearl Harbor attack.

8 December 1941 A Japanese carrier force attacks Pearl Harbor.

Wake Atoll is attacked by 36 Betty bomber planes from bases in the Marshall islands.

11 December 1941 Japanese attempt landing on Wake and are repulsed by coastal gun fire. Two destroyers sunk.

16 December 1941 U.S. task force 14, built around U.S.S. Enterprise leaves Pearl Harbor to mount relief operation.

23 December 1941 Japanese successfully land on and conquer Wake Atoll. The U.S. garrison surrenders.

24 December 1941 U.S. task force 14 is recalled.

January 1942 Captain Sususmu Kawasaki, IJN, appointed island/atoll commander.

January 1942 Japanese begin emplacing guns

12 January 1942 U.S. Prisoners of War are evacuated on Nitta Maru from Wake for confinement in Japan and China

24 February 1942 First U.S. carrier strike on Wake and photographic reconnaissance operation. TF centred around U.S.S.Enterprise and heavy cruisers U.S.S.Northampton and U.S.S.Salt Lake City. 126

31 July 1942 Photographic reconnaissance mission flown by B-24 from base on Midway

August 1942 Main thrust of Japanese defense development begins

30 September 1942 U.S. prisoners of War are evacuated on Tachibana Maru from Wake for confinement in Japan and China. 100 PoW's remain on the island.

13 December 1942 Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara, IJN, appointed island/atoll commander

23 December 1942 First land-based night-bombing bombing mission flown by 26 B-24D planes of the 307 th Bombardment Group (VII th Bomber Command) from base on Midway [127] , documenting the feasibility of such missions.

22 January 1943 Photographic reconnaissance and bombing mission flown by 6 B-24D planes of the 307 th Bombardment Group from base on Midway.

25 January 1943 Photographic reconnaissance and bombing mission flown by 6 B-24D planes of the 307 th Bombardment Group from base on Midway. One zero shot down (confirmed) and four other possible shoot downs.

Early 1943 The Japanese garrison on Wake is strengthened by 600 IJA troops

15 May 1943 Bombing mission flown by 9 B-24D of the 371 st Bombardment Group from base on Midway. Four zeros shot down (confirmed), 1 probably shot down and 8 hit. 5 B-24D's of the 372 nd Bombardment Group also from Midway did not reach the target.

8 July 1943 Eight B-24 make landbased strike against Wake from base on Midway

Summer 1943 The Japanese transport Suwa Maru torpedoed by a U.S. submarine and ran aground on the western reef to prevent sinking.

6-7 October 1943 Major U.S. carrier strikes against Wake by task Force TF 14. The aircraft flew 510 sorties, dropping 340 tons of bombs, while fleet units bombarded the island with 3198 rounds of 5" and 8" projectiles.

7 October 1943 The remaining 98 U.S. civilian prisoners of war are executed by the Japanese atoll commander, Rear Admiral Sakaibara, fearing an American invasion.

1 January 1944 The Akagi Maru, the last surface supply ship to arrive reached Wake from Kwajalein.

January 1944 The Japanese garrison on Wake is strengthened by 1,000 IJA troops

January-May 1944 996 US sorties flown against Wake, dropping 1079 tons of bombs and surface bombardments totalling 7092 5" and 6" projectiles.

29 January 1944 Two squadrons of Coronado flying boats raid Wake Atoll from Midway.

4 February 1944 Two squadrons of Navy Coronado seaplanes attack Wake from base on Midway.

24 March 1944 B-24 raid on Wake Atoll.

23 May 1944 Carrier raid on Wake.

September-October 1944 Repeated strikes by AAF B-24's

January-June 1945 Repeated strikes by US Navy shore-based VP squadrons, mainly from Enewetak.

20 June 1945 B-24 raid on Wake Atoll from Enewetak.

28 June 1945 The last Japanese supply submarine reaches Wake Atoll.

July 1945 Major surface bombardment.

July 1945 The U.S. DD Murray intercepts the Japanese hospital ship Taramago Maru bound for Make to evacuate the weak and wounded. [128] Permission was given an on the return trip 974 evacuees were counted.

13 August 1945 Last U.S. carrier raid against Wake

17 August 1945 The Japanese Emperor calls on the Japanese armed forces to surrender.

2 September 1945 Japan formally surrenders in Tokyo Bay on board of U.S.S. Missouri.

4 September 1945 Rear Admiral Sakaibara signs the surrender papers on board of U.S.S.Levy standing off Wake and the U.S. Flag is run up on Wake. .